Published on February 23, 2018

The topic of friction ridge sufficiency can be a very complex subject. Sufficiency has several applications within friction ridge science. For example, sufficiency for identification, sufficiency for elimination, sufficiency for AFIS searching and for saving to an AFIS database, sufficiency for exclusion and sufficiency for comparison. Each of these sufficiency decisions are based on the quantity and quality of information in a print and each application may have a different threshold. When it comes to Live Scan prints, a dimension I find myself concerned with is the quality of the known print record. A key component of quality is clarity, it should be one of the most important considerations in any print analysis. It has been my experience that clarity is usually an afterthought in an examiners ACE (Analysis Comparison and Evaluation) process. Clarity is often grossly overstated in friction ridge analysis reports and bench notes, yet clarity is crucial in the proper analysis of latent and known prints. Quality and quantity have a symbiotic relationship in print analysis. The higher the quality the lower the quantity required for latent print or known print sufficiency.

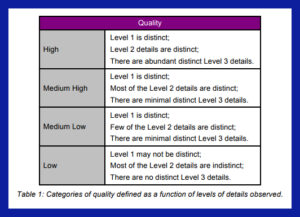

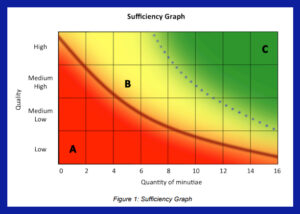

SWGFAST (Scientific Working Group on Friction Ridge Analysis, Study and Technology), which is undergoing a metamorphosis within the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) umbrella as an Organization of Scientific Area Committee (OSAC) Friction Ridge Subcommittee, addressed theissue of sufficiency nicely in their “Standards for Examining Friction Ridge Impressions and Resulting Conclusions (Latent/Tenprint)” version 2.0 document with the following table and graph.

Using these illustrations, you can easily see the relationship between quality and quantity. That said, print quality and quantity, along with specificity is highly variable in any latent print and to

some extent in a known print. So, with all respect to SWGFAST, these illustrations can oversimplify the issue of print sufficiency.

As a latent print examiner, is there anything more irritating than comparing a latent print to a known print and realizing that the latent print is better quality? There is no shortage of technical

errors a fingerprint taker can make while acquiring a set of prints from an individual, but Live Scan records can easily add to the depreciation of the quality within a print record.

Live Scan print records often look wonderful on the monitor, but surprisingly many agencies choose to print the records and discard the digital record when the electronic storage in their Live

Scan systems runs out. When Live Scan records are printed, they almost certainly lose a quarter, if not a half, of the clarity potential regardless of the quality of the latent print they are being

compared to. The effect of which is to require the examiner to find a higher quantity of minutiae or level two features in a latent print to be able to resolve it. Level three details seldom, if ever,

print reliably and depending on the printer setup you may even have to contend with pixelated ridges. One agency, which will remain nameless, chose to print out the Live Scan record from

the contributor and then scan the printout into an AFIS record; I kid you not!

Using the sufficiency graph, if you have an excellent level of quality in both the latent and known prints you may only need 7 level two features to resolve the comparison. If you are using

a Live Scan system and have minimal distinct third level features and some clarity or deviation issues you may need 11 level two features before you can resolve the same latent print

comparison.

Several agencies have also turned to using various hand conditioners for people being printed on Live Scan systems in support of obtaining better images. In many cases, the over-moisturizing of

hands obliterates any level three detail. But to the untrained eye the prints may look acceptable. Again, consider the SWGFAST quality table. In these cases, you could lose as much as a third of

your quality metric using hand conditioners alone.

Another concern is that when examiners are not used to seeing extremely high-quality prints, they become apologists for poor-quality known records and often overstate the qualitative value

of the prints. After all, in their world, that’s as good as it gets. This happened a long time ago when prints were faxed between agencies, we just expected faxed prints to be as good as we

were going to get. The better agencies had policies in place that prohibited faxed prints from being compared to latent prints for obvious reasons.

How can we overcome the quality depreciation issue in Live Scan records? In my opinion, any agency not saving all the electronic records they create with live scan systems is doing themselves and their constituents a disservice. When they retain the electronic NIST file created by live scan systems, they can easily use a NIST viewer or some other means to view and/or export the electronically captured friction ridge record. Electronic records are best viewed electronically. And today, when digital photography and latent print digital image enhancement are normal processes, the comparisons should be made digitally as well. When you choose to purchase a live scan system, agencies should make sure they purchase a means to store and electronically retrieve and review every record their system creates.

Live scan systems can create many problems for forensic practitioners. The clarity of the record will have a significant impact on future sufficiency decisions, if and when the prints require a

comparison to a latent crime scene print.

Shane Turnidge

www.sstforensics.com